For most millennials I know, the American dream of homeownership doesn’t just feel far away, but impossible. Especially if you live in an urban area, if your own parents didn’t own a home, if you’re saddled with student debt — it doesn’t matter if a mortgage payment might be equal to what you’re paying in rent when you’re struggling month to month, barely putting enough aside to save for an emergency, let alone a down payment.

And it doesn’t just feel like fewer of us are buying homes. Statistics bear it out: According to a 2018 report from the Urban Institute, as of 2015, the homeownership rate for millennials (then age 25 to 34) was around 37% — that’s 8 points lower than the percentage of Gen X’ers or boomers at the same point in their lives. According to the study, there are multiple, intersecting reasons for this, all of which will likely sound familiar to millennials shut out of the market: We’re getting married and having kids later; we have far more student debt; and many of us are drawn (by necessity or choice) to urban areas with “inelastic housing supplies,” where both home prices and rental costs have skyrocketed.

When I lived in Brooklyn, I’d gaze at the prices for a studio apartment in my neighborhood (between $700,000 and $1 million) or a brownstone ($2 million to $5 million) and wonder: Who could ever make this happen? Rich people, sure. But people tend to get rich, at least in part, by owning real estate. To get there, you need a down payment. And if you’re putting your extra money toward child care, or loans, or medical bills — how do you come up with that down payment? And how do you find a home you can actually afford?

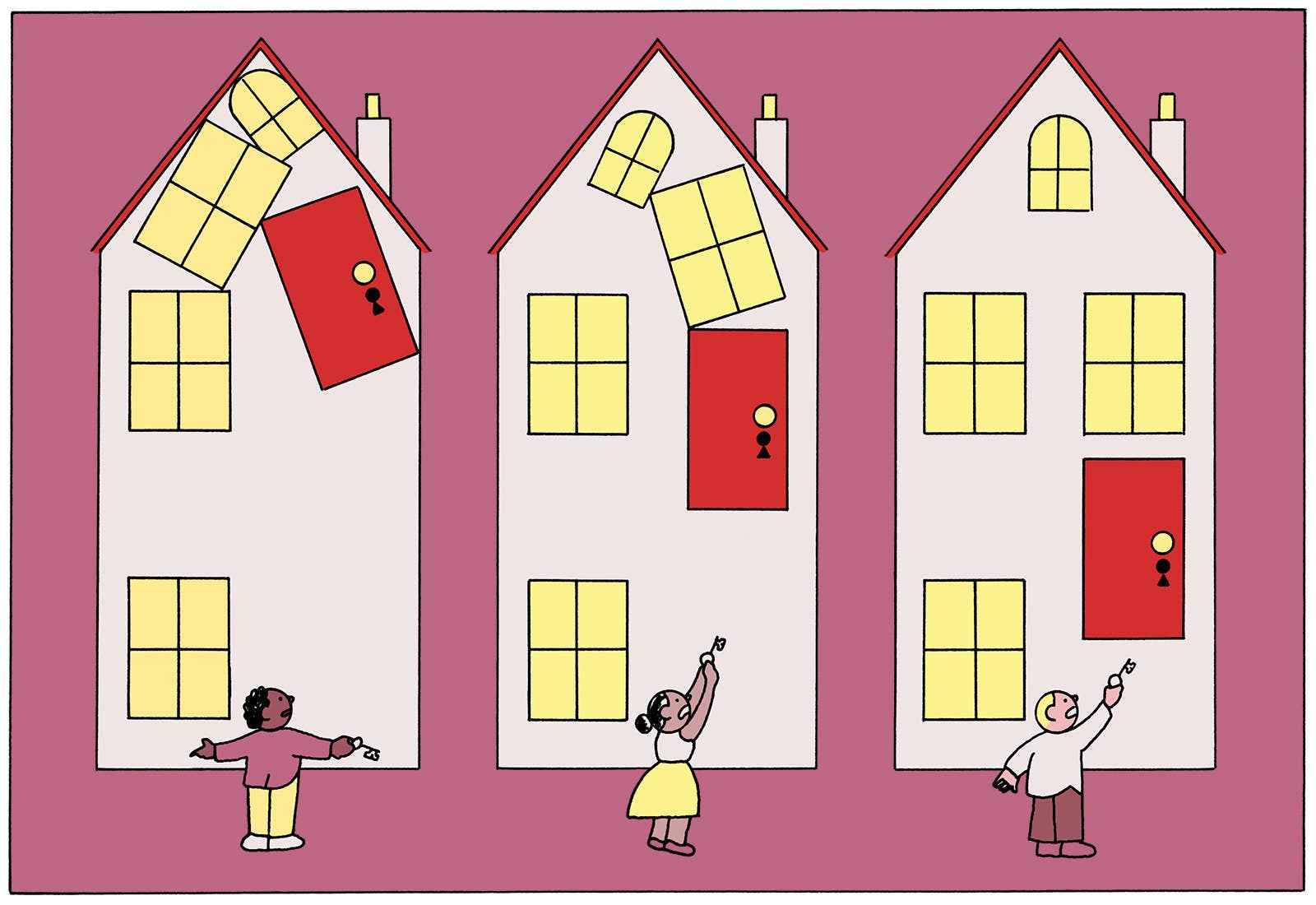

Homeownership, like other forms of participation in the American dream, increasingly resembles an exclusive country club, with membership predicated on who your parents are and your race. To wit: A millennial’s likelihood of owning a home increases 9% if their own parents were also homeowners. While 39.5% of white millennials own homes, the black homeownership rate is just 13.4%, the Asian ownership rate is 27.2%, and the Hispanic ownership rate 24.6%. “Left unchecked,” the Urban Institute study declares, “current trends will result in even greater wealth disparities among white, black, and Hispanic millennials.”

The trends we’re seeing right now in homeownership will reverberate for generations to come — and accentuate the 21st-century parameters of privilege. The difference between people whose family can afford to help with a down payment and people who have no choice but to rent might mean the difference between who can live within 15 minutes of their job and who has to commute two hours, between who’s employed full time and those who depend on contingent work, between who can presume safety in public spaces and whose skin color makes them a perceived threat, between who can pay for college independently and whose children — and grandchildren — will eventually take out their own massive student loans.

I wanted to talk to people within this new reality about how they actually managed to make homeownership work. So I created a survey, and asked readers and Twitter followers and friends of friends of friends: Tell me everything. Tell me how you found the house, how you pulled together the down payment, and how you feel about all of it. Being transparent about this stuff won’t necessarily make buying a home easier for others. But it will hopefully demystify what it takes to make it happen, and help make clear that millennials who don’t own homes aren’t failures. They’re just young people who have faced a dramatically different financial and real estate reality than the generations that came before — a reality that has impacted some more than others.

What follows are 14 stories chosen from over 500 submissions, and they all exemplify, in some way, themes I saw again and again. (Stories have been lightly edited for length and clarity; some names have been changed to protect people’s privacy.) Many people received money from family for a down payment; they chose to buy in an area of the country where homes are markedly cheaper; their parents were homeowners or felt very strongly about homeownership as a mark of adulthood; others are ambivalent about their own homeownership and the way it excludes so many others their age.

The shifts in homeownership aren’t just about capital and equity and down payments and mortgage debt. They’re also about how we think about ourselves, and the places we live — and about how places that remain affordable can change.

We can try to articulate new standards, different from those of our parents and grandparents, for what constitutes success or adulthood. But in this moment, we are still a country very much obsessed with homeownership — despite the fact that just over a decade ago that obsession, and the predatory lenders willing to encourage it, sparked a global financial crisis. What’s clear is that homeownership is still one of the most effective means to transmit wealth and accumulate status. Until that changes, the question of who can own a home — and how they’re able to make it happen — matters.

View the full article here at BuzzFeedNews

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-wordpress-client-uploads/wweek/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/22134054/4430_Housing_Neighborhood_Hollywood_Single-Family_Walker-Stockly_6.jpg)

Sustainability was another key aspect in the design. “The building’s many skylights, each with a different orientation and size, provide natural lighting for the museum’s spaces at all times of the year; its sand-covered roof greatly reduces the building’s summer heat load; and a low-energy, zero-emission ground-source heat pump system replaces traditional air conditioning,” states the firm.

Sustainability was another key aspect in the design. “The building’s many skylights, each with a different orientation and size, provide natural lighting for the museum’s spaces at all times of the year; its sand-covered roof greatly reduces the building’s summer heat load; and a low-energy, zero-emission ground-source heat pump system replaces traditional air conditioning,” states the firm. associations?

associations? Comments such as those have led neighborhood activists who are white or not religious or don’t speak another language to ask: What group speaks for me if not my neighborhood association?

Comments such as those have led neighborhood activists who are white or not religious or don’t speak another language to ask: What group speaks for me if not my neighborhood association?