Our very own, Robyn Hartmeyer, has a wonderful article about her in Bridlemile Magazine.

See crazy before, after photos

Can you recognize a house with “good bones” even when it’s buried in debris? Flippers can. They lay down cash for a dwelling deemed unlivable, then remodel, restore and remake it into a property a new buyer will pay a bundle for. Or so they hope.

Check out these before and after photos to see how 10 awful Portland-area homes rose in value when the hammering was done.

A deconstructed, single-story 1965 house was deemed “a major fixer” by listing agent Brian Flatt of Legacy Realty Group. The 0.29-acre property at 352 N.E. Enyeart Place in Hillsboro sold for $307,125 in December 2018.

After it was “taken down to studs” and rebuilt, it went put back on the market at $549,900. “Can I just say WOW,” says listing agent Sherry Hawkins of Knipe Realty ERA Powered.

A ranch-style house, built in 1960 on a 6,098-square-foot lot in Northeast Portland’s Parkrose neighborhood sold for $150,000 in March 2019.

The structure was described at the time by listing agent Beth Kellan of Windermere Realty Trust as one that “cannot be financed even with repairs… a very heavy fixer or tear down.”

The remodeled, expanded house at 10908 N.E. Marx St. is now back on the market at $269,999. It has three bedrooms, two bathrooms and 1,209 square feet of living space with hardwood floors and new appliances, says listing agent Chris Wagner of Mal & Seitz.

The tri-level house, built in 1978 on a 10,000-square-foot lot in Sherwood, was for sale as a cash-only transaction since it “not financeable in this condition,” according to listing agents Donald Johnson and Jay Westfall of Premiere Property Group. It sold for $277,000 in November 2018.

Fast forward after a complete remodel of the house with four bedrooms, 2.5 bathrooms and 2,471 square feet of living space: The property on Southwest June Court sold for $430,000 in June 2019 by listing agent Jennifer McNair of All Professionals Real Estate.

View the full article here at The Oregonian

As it gets more expensive to live in Portland, officials have been pondering: What to do when the city’s vaunted neighborhood associations seem to act more like swank homeowner

The answer reached by a government committee – to erase neighborhood associations from the city code altogether – has dozens of neighborhood leaders sounding the alarm that their renowned system of civic engagement is under threat.

That proposed undoing has board members of Portland’s nearly 100 neighborhood associations drawing battle lines against the city committee, officials in the Office of Community & Civic Life – the bureau that works with neighborhood associations – and the bureau’s commissioner-in-charge, Chloe Eudaly.

It has also surfaced long-simmering tensions. Neighborhood activists view themselves as representatives of grassroots Portlanders and the distinctive parts of town they inhabit. Detractors see the associations as entrenched, overly powerful voices for homeowners, who tend to be older, white and opposed to housing density, homeless shelters and other development helpful to a growing city’s health.

Sam Stuckey, for example, said neighborhood associations “are just there to be obstructionist and delay housing we desperately need.” Despite that qualm, Stuckey, a 32-year-old architect, sits on the Mill Park Neighborhood Association board.

“I think there’s some level of truth to that,” said Stan Penkin, chairman of the Pearl District Neighborhood Association, though that line of thinking fails to acknowledge “all the things that neighborhoods do that are positive.”

John Legler, a board member of the Creston-Kenilworth association, sees it differently. In his view, the city wants to “get rid of neighborhood associations because we cause too much trouble” over land use issues. If the committee gets its way, he said, “We will exist in form but without legitimacy.”

At a meeting of the committee in June, many board members also insisted their groups are more diverse than critics acknowledge.

“I am neither old, nor rich, nor white,” said Elizabeth Deal, 33, a nurse and leader of the King Neighborhood Association who is Asian.

Erasure of the associations from city code would have sweeping effects, though the full extent is unclear. Officials say the worries of neighborhood association champions are overblown.

At its core, the change would remove the special powers of neighborhoods to officially weigh in on city government actions. The most notable of those are zoning decisions adopted by the City Council, often at real estate developers’ urging. Currently, neighborhood associations must be consulted on such decisions and may formally appeal them at no cost.

Activists also worry the update is a pretext to cut off neighborhood associations from city-paid event insurance. They say doing so would prevent family-friendly events like block parties and also push some associations into financial ruin.

Neighborhood matters would also be less transparent, as the committee plans to remove requirements that associations allow the public to attend board meetings, make a record of votes and preserve copies of documents.

Activists have also cried foul about the code change process. Neighborhood board members say they were not notified of committee meetings. While officials are adamant notices were sent, members of associations across the city said, without fail, that was untrue. And a survey about the code change, which garnered more than 1,000 responses, was seen as insufficient by officials because 69 percent of respondents were white.

In a challenge to the conventions that have underscored more than 40 years of local activism, Eudaly, the commissioner in charge of outreach to neighborhoods, said many Portlanders view themselves less as members of neighborhoods than as a part of ethnic, religious or other non-geographic affinity groups.

“Personally, I am more likely to identify as someone in the disability community or as a renter than as a neighborhood resident,” the commissioner said.

Winta Yohannes, Eudaly’s aide assigned to the code change effort, said the complaints of neighborhood association board members do not reflect Portlanders’ views. “Why should we elevate them over other groups?” Yohannes said.

Asked to provide an example of another group that should be on equal footing, Yohannes said Portland United Against Hate, a coalition of 70 organizations that track and respond to “acts of hate,” according to a city webpage.

Comments such as those have led neighborhood activists who are white or not religious or don’t speak another language to ask: What group speaks for me if not my neighborhood association?

Comments such as those have led neighborhood activists who are white or not religious or don’t speak another language to ask: What group speaks for me if not my neighborhood association?

The proposed code strongly states Portland is an inclusive, welcoming city. It directs the civics bureau to connect Portlanders of all backgrounds with their government, facilitate discussions and develop “learning opportunities that focus on culturally-empowering civic engagement through community-based partnerships.”

Neighborhood association leaders say those are admirable goals but fail to acknowledge the role that neighborhoods play in making Portland vibrant. Far from being heartless NIMBYs, neighborhood leaders say they are instead focused on the mundane but important work that City Hall mostly ignores.

Consider Allen Field. His foray into neighborhood politics began 15 years ago over a typical small-time issue: dog parks.

The board of the Richmond Neighborhood Association was stacked with “dog haters,” said Field, 58, an attorney in private practice. So, he ran for election to the board and recruited other canine admirers to do so. The slate won and used the association’s influence to support the designation of a section at Sewallcrest Park for dogs to roam off-leash.

As a process-oriented lawyer, Field said he is greatly concerned about the city’s plan to remove open records and meetings requirements from applying to neighborhood associations.

“I want things to be open and transparent,” he said. “I believe in notice and being heard. Due process rights.”

Being active in neighborhood matters is rarely about complex land use decisions, he added. Instead, his involvement focuses on graffiti removal, coordinating movie screenings in public parks, trash clean-ups and tending community gardens.

“We’re a city of neighborhoods,” Field said. “And neighborhood associations do things that no other groups do.”

One of the things neighborhood associations do is slow or stop development.

Take leafy neighborhoods like Laurelhurst, where residents shielded themselves from development by seeking a historical area designation. Or Eastmoreland, where neighborhood leaders stopped construction of two homes by launching a protest against the felling of three sequoia trees. And the Mt. Scott-Arleta neighborhood, where bitter opposition to a homeless shelter, spurred on by a neighborhood association leader, has complicated the project.

Using their powers to appeal zoning decisions free of charge, neighborhood associations like those in the Pearl District or Old Town have tried to stop construction of office and condominium towers with varied success.

Critics note those boards may appeal free – and therefore slow developments’ progress – even if the challenges are later deemed frivolous. The fees are waived even for neighborhoods where residents have pooled funds to hire land-use attorneys who charge tens of thousands of dollars to challenge housing density efforts.

Housing and renter advocates have an ally in Eudaly, who said the city government needs a new paradigm for engaging residents.

Yet concerns that the city wants to eliminate neighborhood associations are off the mark, she said. The groups will continue to exist and be “a critical part of what we do,” Eudaly said, adding that the notion she wishes to undermine neighborhood associations is “absurd.”

Suk Rhee, director of the civics office, said the code change is not about “the fate of neighborhood associations” and reducing the groups’ influence “is not a topic that we’ve had.”

The code change committee is supposed to recommend updated language to the City Council in July. It’s unclear if it will. The panel was scheduled to approve the changes at its meeting on June 26, but it could not establish a quorum necessary to hold a vote when a majority of the members failed to attend.

Penkin, the Pearl District leader, said neighborhood associations, ethnic and religious groups and immigrant communities tend to advocate for the same neighborly ideals. Divides are mostly a matter of perception, he said, and passions tend to erupt only when broad changes are afoot.

“This goes back many, many years,” Penkin said. “Everything’s complicated.”

View the full article here at The Oregonian

Beaverton was chosen as one of Apartment Therapy’s Coolest Suburbs in America 2019. We showcased the burbs nationwide that offer the most when it comes to cultural activities, a

The living is easy in Beaverton, a suburb of Portland, Oregon. Neighbors are chatty. Bike trails to neighboring towns and downtown Portland abound. Hop in your car to dozens of box stores minutes away. It seems like everyone composts. Parking is readily available and free. There’s never a line at the post office. City employees return calls swiftly. I could go on. Have I mentioned that all aspects of life are comically uncomplicated? Especially compared to a stint in Manhattan? They are.

Beaverton particularly excels at public spaces and programming: Well-maintained trails weave through mossy forests right out of “The Hobbit,” in a dozen residential neighborhoods. Full rosters of movie nights and festivals fill warm evenings.

Get here sooner rather than later, because housing prices continue to rise. If you envision the West Coast as a very expensive block of cities, the Portland region is the cheapest destination on an overpriced block, which will continue increase in price. Beaverton’s many imports from L.A. and San Francisco constantly say things like “I would’ve moved here a decade ago, if I’d known how nice people are.”

Editor’s note: Beware that locals scratch their heads at the Beaverton city map, which is inexplicably oddly shaped, with Beaverton entirely circling multiple downtown areas. The main impact on locals is that many residents who appear to live in Beaverton technically do not, and thus miss out on cheap parks and recreation classes. This guide covers the Beaverton area.

Average rent price:

$1,337, according to Rent Café.

Median house price:

$392,200, according to Zillow.

Price per square foot:

$223 in Beaverton, vs. $231 in the surrounding metro area of Portland/Vancouver/Hillsboro, according to Zillow.

Walkability score:

48, according to Walk Score.

Median household income:

$64,619 according to Census data.

Population:

97,000, according to the City of Beaverton.

View the full article here at Apartment Therapy

The plan to bring Major League Baseball to Oregon is rounding the bases, and its founder believes this summer is going to be a grand slam.

You’d be forgiven for thinking the plan to build a Major League Baseball stadium in Portland has struck out. Or at least faced a rain delay.

The Portland Diamond Project, a group of investors with their hearts set on building a major league baseball stadium in Portland hasn’t made a peep since April, when they revealed design concepts for the proposed waterfront stadium.

Not that the Diamond Project has stayed out of the news. Recently a story on Oregonlive.com made it seem like the project was about to stumble. The article concerned the group’s exclusive access to its preferred building site, a 50-acre marine cargo terminal in Northwest Portland.

The exclusivity agreement with the Port of Portland is set to expire at month’s end, meaning the project could end up having to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to keep the spot reserved.

But according to Craig Cheek, founder and president of the Portland Diamond Project, the Port of Portland agreement isn’t a cause for concern. “We’ve had a lot of discussion with the port. Everyone still wants to help get this thing through,” he says.

According to Cheek, the Portland Diamond Project is engaged in a “city-led process to pour over the viability of the port site,” meaning that state and local authorities can speed up or slow down the process, depending on their inclination. The site still faces zoning and transportation issues that need to be resolved before the build.

But it’s important to note that although plans to build a stadium have been around for a while, the situation with the Port of Portland is only 10-weeks old. “We have the support of the city. We have support of the bureau heads.” says Cheek. He adds talks with the city are “going very well.”

Despite the Port of Portland’s deadline, Cheek believes the city, the business community and the public at large are warming up to the idea of a waterfront stadium.

“It would be the most transformative site as far as the city is concerned,” he says, referencing the need for development in the area. “You would create a new Northwest edge to the city. Our project would bring new life and a whole new district there.”

The stadium would likely be a windfall for local businesses, and not just food and entertainment. The project could introduce a civilian ferry to make use of the waterway. Cheek has also floated the idea of a completely carless stadium, a welcome relief to Northwest Portland, which already faces monumental parking problems.

Another reason to believe the project is about to swing for the fences? It’s star-studded, ever-growing list of backers, including Seattle Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson, his supermodel wife Ciara, former Chicago Cubs player Darwin Barney and Harvey Platt, retired CEO of Platt Electric. The project has raised $1.3 billion already, nearly half their $3 billion estimate.

On the local front, Olympia Provisions and Breakside Brewery have already tested new products at Diamond Project events, and the project’s swag is selling like hotcakes.

Though there has been much chatter from the dugout lately, the project isn’t going to be silent much longer. “We’re going to be very active in the business community over the summer,” says Cheek. “We’re going to be talking to businesses small, medium and large to get their support.”

But backing from the city and the business community are only two parts of a three-piece puzzle. Not wanting to repeat New York’s Amazon headquarters disaster, in which the e-commerce platform failed to garner broad public support for its new headquarters, Cheek says public support will be a critical element moving forward.

“We’ve encouraged fans to help us create a groundswell for [the stadium.] Thirty-three thousand people have already signed our petition, and we want to grow that number up to 50,000 in the coming weeks.”

Not only could the stadium be an economic grand slam, the project would also introduce Oregon’s sustainability values to major league sports. When completed, the new ballpark could be the most sustainable professional stadium in the country.

For reference, the greenest sports stadium in the nation holds gold certification from the U.S. Green Building Council. “We want our stadium to be the first one to reach platinum,” Cheek says.

As of now, the Diamond Project has its eye on the ball. The project’s summer marketing push is about to commence, and with a few MLB team’s futures up in the air, the project could be coming to a head at just the right moment.

But for all of his dreamy ambitions about revived waterfront, budding baseball culture and sustainability dreams, Cheek’s message to the business community is far more matter-of-fact.

“Portland is in competition with other places trying bring this kind of project to their city,” he says. “If we don’t jump on this, someone else will.”

View the full article here at Oregon Business

IF YOU’RE CRUISING AROUND PORTLAND, Oregon, and come across across a six-foot-tall cut-out of Patrick, the pink, portly starfish from SpongeBob SquarePants, chances are good that Mike Bennett left it there for you to find.

For the past few months, Bennett has been busy with plywood, paint, and power tools, speckling his front yard and the city streets with playful, oversized figures. It all started after a snowstorm, when he was noodling over his collection of Calvin and Hobbes books that his parents had recently shipped to him and thinking about a scene where Calvin makes a big snowman. Bennett hadn’t had a front yard in years, and wanted to figure out how to make it fun. What if the delight of some mounded-up snow could last all year, and never run the risk of melting?

He headed to Home Depot, came back with a jigsaw, and went to town on wood from a nearby ReBuilding Center. Bennett, who was once active on the short-video app Vine, where he  recreated scenes from movies and TV with little paper dolls, began to fill the yard with pop-culture characters. “Familiar stuff brings more smiles to people’s faces,” he says.

recreated scenes from movies and TV with little paper dolls, began to fill the yard with pop-culture characters. “Familiar stuff brings more smiles to people’s faces,” he says.

And then he took the show on the road—within reason. “I’m a pretty big baby when it comes to trespassing,” he says, and he’s also careful to avoid damaging property or plants. He’ll sometimes fasten his wooden characters to light posts, trees, or telephone poles with a few hooks and twine. His information is printed on the back of the figures, so if someone gets in touch to say that they want one to come down, he can swing by and grab it. (So far, he says, he hasn’t encountered any issues.) To make it easy to keep an eye on things, he installed them along the routes he tends to follow each day as he drives around for his day job as an assistant for a real estate company. “They’re my babies now,” he says. “I like to check in on them.”

Bennett loves a good scavenger hunt, and invites people to go out looking for the figures he’s scattered around Portland. (He sometimes drops location hints on Twitter, Instagram, or Reddit.) Taking a cue from a geocaching log, he affixed a little form to the back of each one. There, visitors can jot down their name, the date, and a positive thought.

Some of the signs also nod to culture and quirks that are more particular to Portland. The city famously hatched The Simpsonscreator Matt Groening, and some of the show’s characters borrow their names from Portland streets. Bennett decided to play that up by installing a cutout of Homer’s chummy neighbor Ned Flanders on one corner of NE Flanders Street. When he saw the street sign and made the connection, Bennett thought, “What? Come on,” he recalls. It just seemed too perfect to pass up. He’s also setting his sights on slightly more out-there local lore. “Oregon being the way it is, we’re into Sasquatch,” he says. By August, he hopes to make more than a dozen Bigfoot cutouts, each sporting different proportions and fur colors.

In the more immediate future, he’s planning to confetti the city with little cutouts of Diglett, the petite, pink-nosed Pokémon that sticks its head out of the ground. Bennett intends to make a brigade of the little guys—about 100 in all—with scrap wood he’s accumulated from his larger-scale figures. He’ll tamp them into dirt around the city over the course of June. Each creature will be about five inches tall, and anyone who finds one is welcome to adopt it and make their own yard or windowsill a little more wonderfully weird.

View the full article here at Atlas Obscura

TILE

“Always double-check your tile quantities and purchase more tile than you think you will need. We recommend 10–15 percent for waste and cuts,” says Megan Coleman, cofounder of local modern tile maker Clayhaus. She adds, “if you are going to go busy on your countertop, go simple on your backsplash, and vice versa. Only one can be the star.”

HOUSE-CLEANING

“Add cut lemons or limes to vinegar and let steep a month to make an aromatic natural cleaning concentrate,” says Gina Ross, owner of local housecleaning and organizing service Green Clean by G. “You can get creative and add mint, rosemary, or essential oils. Plus, she notes, the concentrate looks pretty sitting on a counter in a mason jar. Add a ¼ cup to a spray bottle filled with water or dump ¼ cup in your mop water—just don’t use vinegar-basedcleaners on marble, granite, or stone.

PEST CONTROL

Want to keep rodents out of your house? Brandon Clark, owner of Get Smart Rat Solutions, says to quit feeding backyard birds and squirrels. “A bird feeder is like cocaine for rodents,” he says. “If food is available year-round, [rats] will breed year-round—and two rats can produce 1,500 offspring in a year. It’s mind-boggling.” The time to get a pro involved? “As soon as you see something in the house,” he says. That means there’s already a breeding population underneath your house or in your attic.

ENERGY

“A home’s energy system is made up of individual components. Replacing windows without installing insulation or upgrading your heating system might not have the impact you’re seeking,” says Stephen Aiguier, founder of eco-friendly Green Hammer Design Build. “Hire an experienced firm that can help you prioritize energy-efficiency upgrades that will save you money, reduce your carbon footprint, and improve the health of your home.”

PAINT

“Painting is one of the easiest ways to transform space. But it’s very disruptive, and it always takes longer than you think.” says local painter and artist Michael T. Hensley of MTH Painting. “Don’t have your friends come over and do it for pizza and beer. People try to save money that way, and it [rarely] looks good. Take your time in choosing colors. Cleaning, especially kitchens and bathrooms, where there’s a greasy residue is important before you start painting. Paint the ceiling first, then the trim, then you cut in the walls. It’s easier to cut the wall into the trim than vice versa. Also, use FrogTape on the trim. It’s moisture activated, so it seals itself up when the paint hits it.” (No website, email mthpainting@gmail.com)

ORGANIZATION

“Organization is kind of having a moment, with everything going on with Marie Kondo,” says professional organizer Clementine Hacmac. “One of the things I believe in most is there’s not a single system for every person …. Decide what works for [you]. I’m a big fan of organizing things in rainbows—like books. I love rainbowtizing. It always looks really beautiful and clean and super-intentional. And that’s one of the tricks of organizing: when it looks beautiful, you are more likely to keep it up. Getting rid of stuff doesn’t mean you’re losing anything. It means you’re opening the possibility to have only that which truly serves you in your life.”

PLUMBING

“Be mindful of your washing machine hoses,” says Craig Anderson, owner and vice president of Craig Anderson Plumbing. “They’re made of rubber. The rubber breaks down. The chlorine in the water, sunlight, heat, all that affects rubber in negative ways. When a washing machine hose fails, you’ve got, as a result, a flooded house. So keep an eye on those hoses. Make sure they are changed out every five to seven years. That could save you a lot of heartache.”

GARDEN DESIGN

“Most of the time [people] buy one of this [plant] and three of those and one of that, but really you should be buying 20 of one thing,” says Peter Lynn, garden designer at Pomarius Nursery. “In order to prevent a lot of weeding and spraying or mulching, you overplant, and over time things weed out and you’ll enjoy them.” Lynn also says to let ’em be as much as you can: “The more you [walk] on the beds, the more you trample, the more you compact, the less it grows. You want to limit the amount of time you go in the beds if you can. What you’re trying to achieve is that within a year, you don’t see the ground anymore.”

View the full article here at Portland Monthly

This winter may have been drier than last year’s, when record-breaking snow and rainfall brought wildflower superblooms to national parks and fields across the West, but that doesn’t mean you won’t be able to spot gorgeous blossoms this spring. As temperatures continue to rise, wildflower season is in full swing. Here are some prime spots to catch the blooms.

Washington

Set along the Puget Sound near Bellingham, Anacortes Community Forest Lands holds old-growth forests filled with native berry shrubs that bloom from February to August. Among these, Indian plum, red flowering currant, salmonberry, and red huckleberry are ones to watch for. Later in the spring and into summer, orange trumpet honeysuckle hangs from the trees overhead, and wild Lily of the Valley and coral root orchids blossom underfoot. The real treat is a trek through bald meadows on Fidalgo Island’s Sugarloaf Mountain, where hiking trails give views of spring gold, blue-eyed Marys, fawn lilies, Western buttercup, and red Indian paintbrush. Take a guided hike through the 2,700 protected acres, led by a local steward of nonprofit The Friends of the Forest.

Oregon

Tom McCall Preserve, 231 acres of grassland along the Columbia River Gorge, is home to 300 species of plants, and grants you stunning views of Mount Hood and the Columbia River. Every spring, starting in late February, it’s also home to one of the most incredible wildflower displays in the state. Keep an eye out for grass widows, prairie stars, shooting stars, lupine, and Indian paintbrush. The grasslands are also home to four plant species unique to the River Gorge—Thompson’s broadleaf lupine, Columbia desert parsley, Thompson’s waterleaf, and Hood River milkvetch. Catch the blooms along the Rowena Plateau, near the edge of the River gorge, along a 3.6-mile round-trip hike.

California’s golden coast has long been famed for its poppy-filled plains. Antelope Valley California Poppy Reserve, a state-protected reserve of Mojave Desert grassland in northern Los Angeles County, offers 8 miles of hiking trails through rolling hills of golden poppies, lupine, and coreopsi, from mid-February to mid-May. Though National Weather Service and Park Service officials aren’t confident that rainfall will increase significantly enough in the coming month to warrant another superbloom, the reserve is known for consistent poppy displays each year.

Further north, Death Valley’s famous flower displays begin earlier in the spring at lower elevations, where desert gold, notch-leaf Phacelia, golden evening primrose, and gravel ghost dot foothills until mid-April. As temperatures continue to rise, upper desert slopes and canyons welcome desert dandelion, Mojave aster, indigo bush, and desert paintbrush.

Colorado

Colorado’s sweeping plains and mountainsides are prime for wildflower viewing, especially at the popular Roxborough State Park, 3,245 acres of wild land just southwest of Denver. Naturalist Ann Sarg suggests visiting the park to catch blooms in May, when natives like Nelson’s larkspur, nuttall violet, sand lilies, and mariposa lily bloom along paths like the Willow Creek trail. She also says some natives, like the spring beauty, have already begun to bloom, and that late-blooming varietals like porter aster and Liatris pop up later towards summer. Fellow naturalist Susan Dunn suggests arriving earlier in the morning for flower hikes in order to take advantage of cooler temperatures, and also recommends that visitors hop on the RoxRide, a five-passenger cart driven by a naturalist who can point out the blooms along the way during spring weekends.

Arizona

You might not expect wildflowers to bloom in the deserts of Arizona, but the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix showcases dry-weather flowers that can be found across the state. Prime viewing time in the gardens starts in early March, when they fill with desert wildflowers like firecracker penstemon, blackfoot daisy, and Mexican gold poppies, along with blossoming cact, which bloom along the popular Harriet K. Maxwell wildflower trail.

Just an hour outside of Phoenix, the Boyce Thompson Arboretum is a 323-acre state park committed to the study of drought-toleran, desert-happy plants from all over the world. Come mid-March, spring flowers like desert marigolds, brittle brush, and perry penstemon fill the park’s several gardens with color, and native milkweed attracts monarch butterflies. After April, the park’s collection of cacti, which include ocotillo, yucca, hedgehog, saguaro, and aloes, share their regal blooms.

View the full article here at Sunset

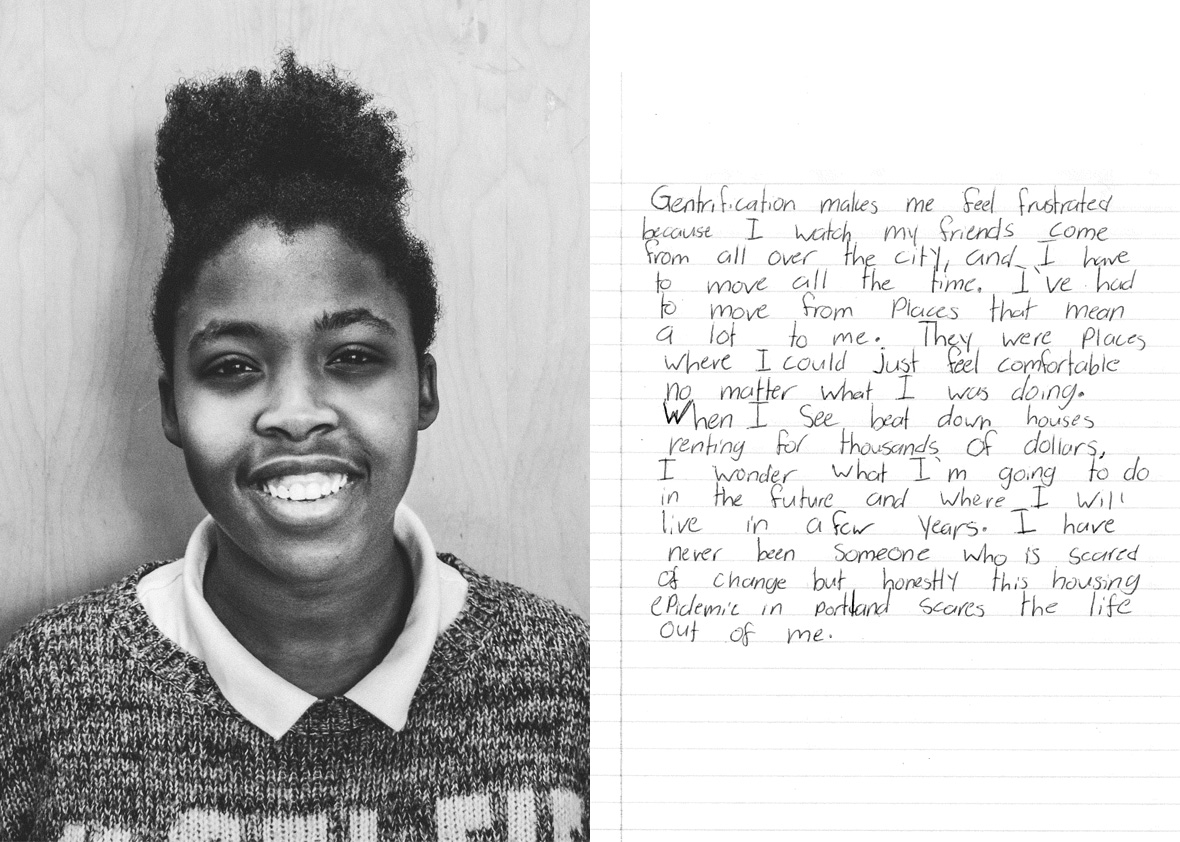

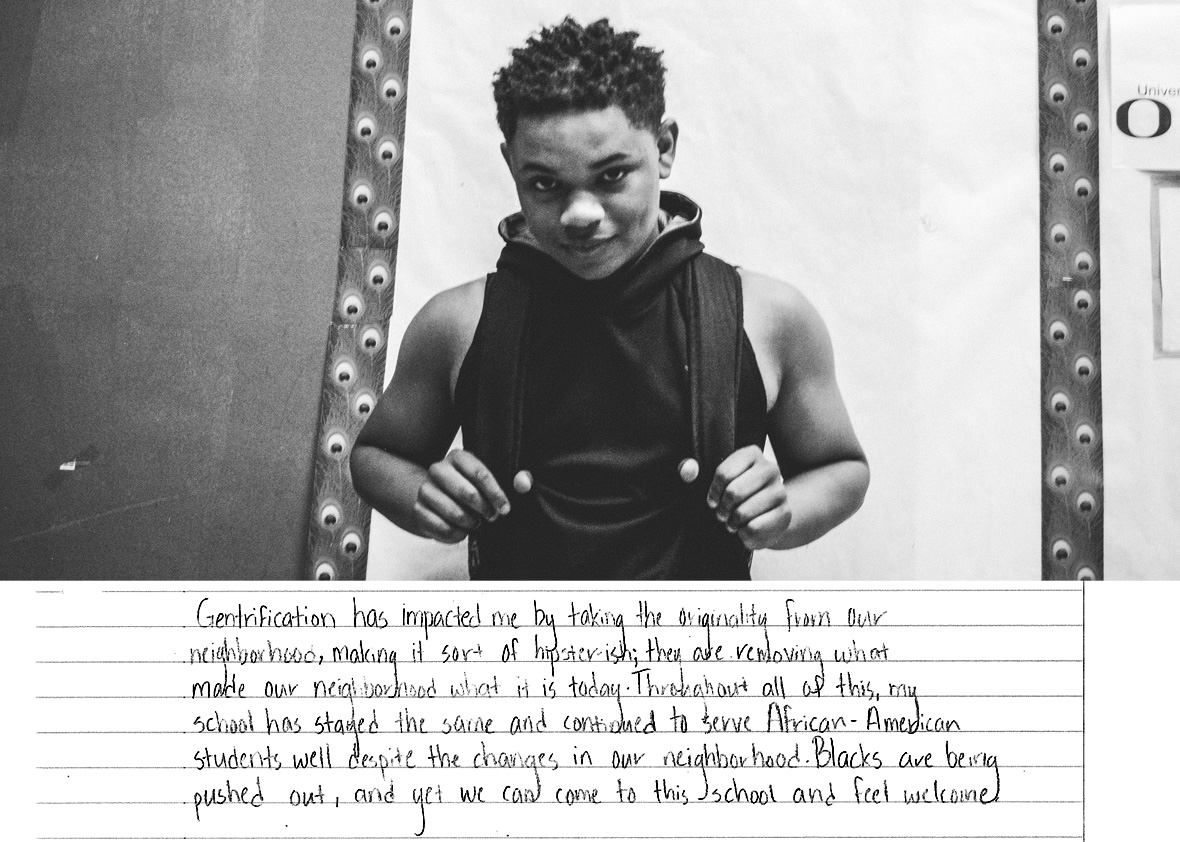

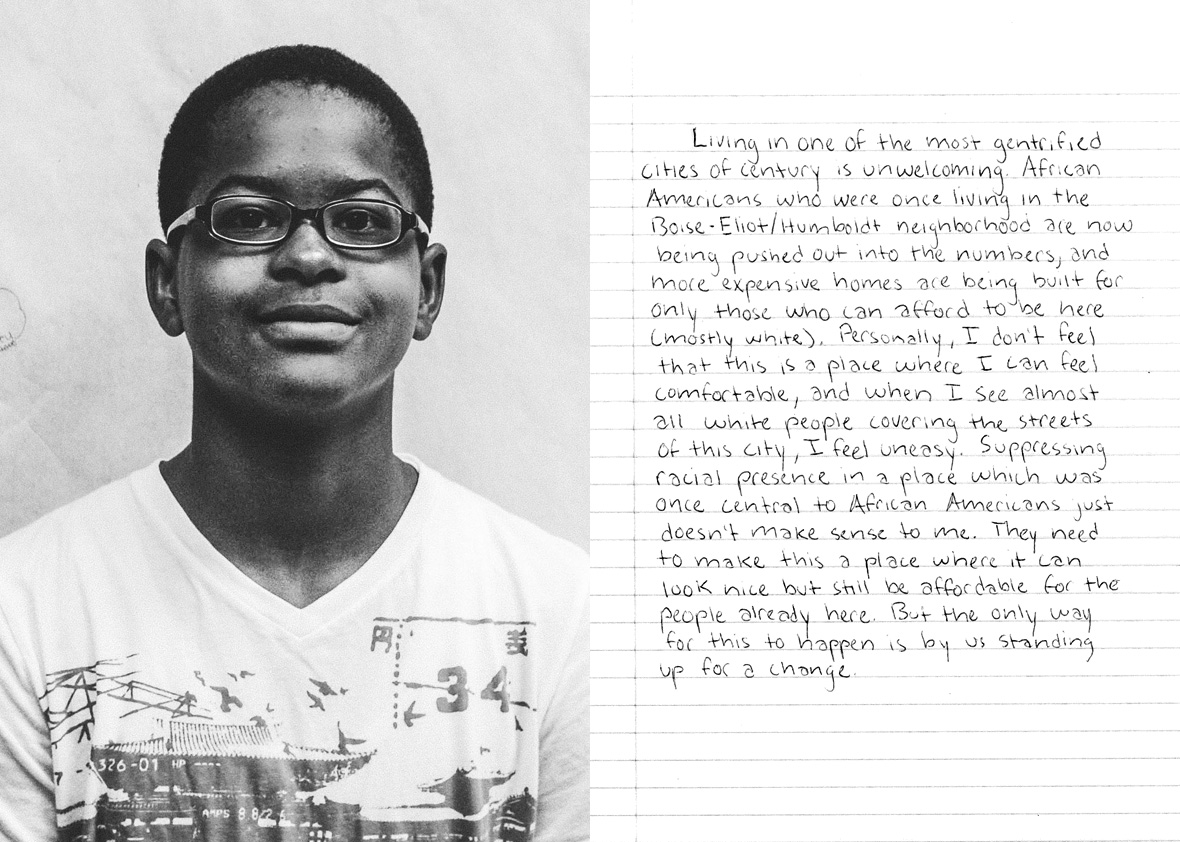

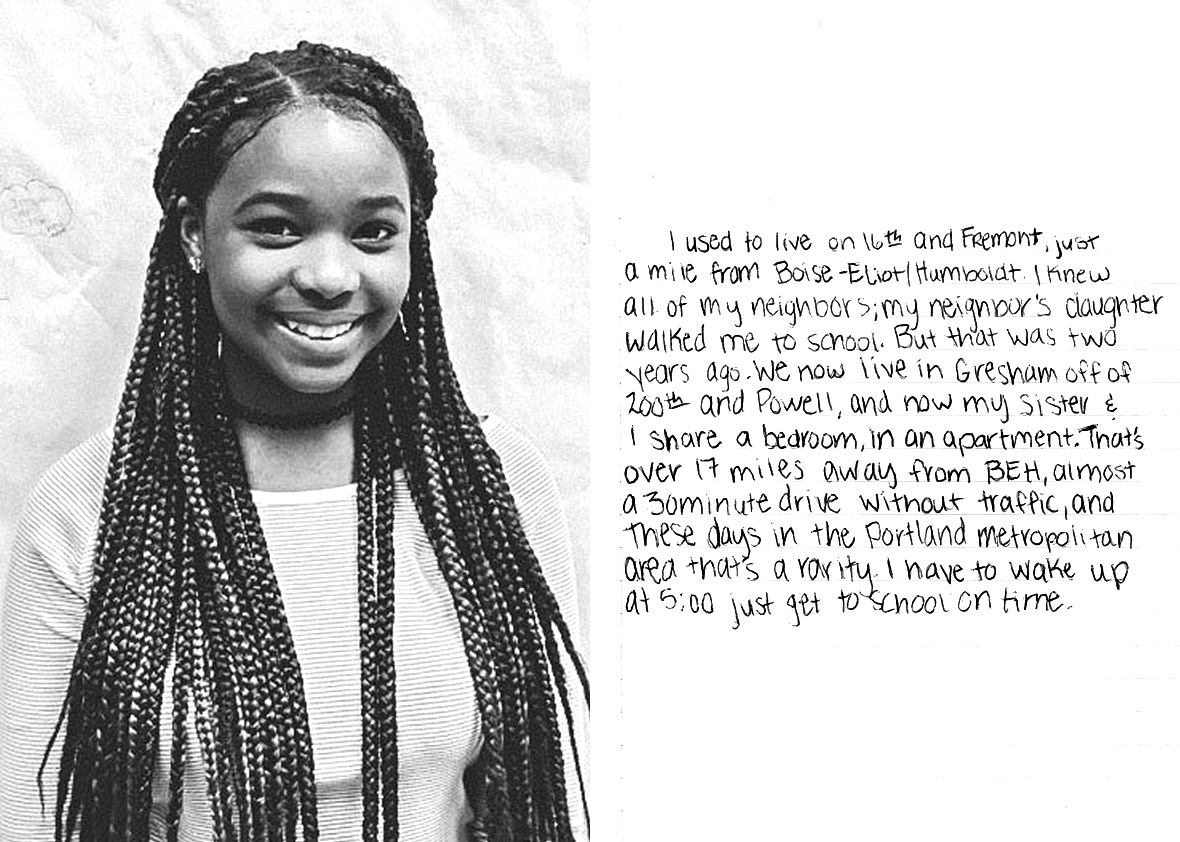

PORTLAND, Oregon—Across Portland’s Albina district, chic cafes advertise pour-over coffee and delicacies such as blueberry basil donuts. On Mississippi Street, hollowed-out school buses and roadside stands sell vegan barbecue and bacon jam empanadas. The street signs read “Historic Mississippi,” a nod to the area’s century-old roots, but it’s increasingly difficult to find spots that don’t evoke the decidedly ahistoric hipster vibe that now makes Portland famous.

a strip mall with a yoga studio and a combo bar and laundromat, the two-story red brick building hasn’t changed much in decades. Unlike the neighborhood’s new residents, a majority of its students are black and low-income. Many of their families have been priced out of the Albina area and relocated to outskirts of Portland, a move known as going “out to the numbers” because of those areas’ numbered streets. So the students take public transportation to attend Boise, a revered institution in Portland’s black community. Most newly arrived white families, meanwhile, transfer their children out of Boise into schools that they consider better—and which are definitely whiter.

a strip mall with a yoga studio and a combo bar and laundromat, the two-story red brick building hasn’t changed much in decades. Unlike the neighborhood’s new residents, a majority of its students are black and low-income. Many of their families have been priced out of the Albina area and relocated to outskirts of Portland, a move known as going “out to the numbers” because of those areas’ numbered streets. So the students take public transportation to attend Boise, a revered institution in Portland’s black community. Most newly arrived white families, meanwhile, transfer their children out of Boise into schools that they consider better—and which are definitely whiter.When neighborhoods gentrify, schools often don’t follow—at least not nearly as quickly.

It’s a phenomenon playing out across America as middle-class white families move into urban neighborhoods that real estate agents might have once called “undesirable.” Think Harlem in Manhattan, Oak Cliff in Dallas, the Bywater in New Orleans, the South Loop in Chicago, or the Mission District in San Francisco. They may be hip destinations with attractive amenities, but most of their public schools don’t get the same love from new arrivals. The problem is particularly acute in Portland, which is already the whitest big city in America and growing whiter.

… Despite the changes in the area, the student body remains a hair under 60 percent black and only 15 percent white. That’s almost opposite of the surrounding neighborhood, which according to the 2010 census is 63 percent white and less than 20 percent black (down from more than 50 percent black in the 1980s, and almost entirely black in the 1960s). School staff say the neighborhood has grown even whiter in the past six years, with the school demographics changing at a much slower rate.

… Despite the changes in the area, the student body remains a hair under 60 percent black and only 15 percent white. That’s almost opposite of the surrounding neighborhood, which according to the 2010 census is 63 percent white and less than 20 percent black (down from more than 50 percent black in the 1980s, and almost entirely black in the 1960s). School staff say the neighborhood has grown even whiter in the past six years, with the school demographics changing at a much slower rate.

This system allows many black students who’ve moved away to petition to attend Boise, but Bacon says even more simply fake their addresses—listing the home of an aunt or a grandmother who still lives near the school. “This school has always served Portland’s black community. They have relationships here—trust,” says Bacon. “The school has delivered for their relatives, and they want that for their kids.”

A West Linn mansion listed for $18 million comes with bidets, a Benihana hibachi table and bragging rights that Bruce Willis slept here.

A West Linn mansion listed for $18 million comes with bidets, a Benihana hibachi table and bragging rights that Bruce Willis slept here.

It’s not the most expensive residential listing ever in Oregon, but the Mediterranean palace on 35 acres, named Villa de l’or (house of gold or mountains), is at the very top right now.

Listing agent Tina Wyszynski of Cascade Sotheby’s International Realty has been quietly trying to sell the ritzy compound at 1707 S.W. Schaeffer Road since November.

Four days ago, she listed it on the Regional Multiple Listing Service’s searchable real estate database, and on Wednesday, she’s inviting journalists to take a tour inside the mansion with marble floors, gold-colored fixtures and crystal chandeliers. Qualified buyers or their representatives can see it anytime.

The house, with 14 bedrooms (not to mention servant quarters) and 10 bathrooms, would be sold furnished. Furniture and decorative accessories cost more than $550,000 when new in 1996. Drapery and upholstery fabrics alone were several hundred dollars a yard.

A member of Wyszynski’s sales team, who asked not to be named, said they are looking for a very specific buyer: Perhaps someone who might want it as a boutique resort.

Or the home could be a “repository for art,” he said, for a deep-pocket collector who sees value in Oregon’s absence of sales or use taxes.

Elaine Wynn, the co-founder of the Wynn casino empire in Nevada, avoided paying as much as $11 million in use taxes in her state by lending the $142.4 million Francis Bacon’s triptych “Three Studies of Lucian Freud” to the Portland Art Museum before shipping it to her Las Vegas home.

Most likely, Wyszynski will find a buyer outside of the state, since, according to research her team has conducted, there are only about 330 people in Oregon who have investment assets of $30 million or more. That’s the bottom line the team decided would be needed to purchase and maintain the 16,359-square-foot residence – larger than the Pittock Mansion — as well as the private soccer field, tennis court, gym, pool, pool salon and horse arena.

Unlike most extreme estates with a sprawling main house, this one doesn’t have detached guest houses or large outbuildings. “It’s not Hearst Castle,” in central California’s coast with casitas as large as 5,875 square feet, said the sales member.

But there is an enormous stone Tuscan-styled wine vault that can store imported bottles and estate wine made from grapes grown in four acres of vineyards.

Don’t worry if the family that built Villa de l’or will be struggling to find a replacement. According to the sales team, they have other homes “just like this one” over the world, including in London, England, and Nice, France.

The husband and wife attended Portland State University and have business interests in the area and donate to local causes, according to documents, but they are only here two weeks a year, said the sales team member.

The complete article and additional photos can be found HERE on Oregonlive.com